Wilson's Sheep

/*Article originally published in April 2019

When you picture the White House lawn, you might imagine perfectly manicured grass, carefully tended gardens, and perhaps the occasional Easter Egg Roll. But for three summers during World War I, the most famous address in America had some unusual groundskeepers: a flock of sheep.

What seems like a mere agricultural preference of the Executive Branch was actually a calculated political move. In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson enlisted this woolly crew to keep the grass trimmed and, by auctioning their wool, raised between $50,000 and $52,000 for the Red Cross war fund, a remarkable sum for the time.

How the Flock Came to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

The story begins with Dr. Cary T. Grayson, Wilson's personal physician and close friend. Grayson contacted his horse racing acquaintance William Woodward, who owned Belair Farm in Bowie, Maryland. Woodward sent along a small flock, 18 sheep in all, by wagon to the nation's capital. Over three summers, that number would grow to 48.

Woodward understood that the idyllic appearance of sheep grazing on the White House lawn was part of the appeal. The image projected exactly what Wilson wanted: a first family leading by example, making sacrifices for the war effort just like everyday Americans.

More Than Just Lawn Care

The patriotic sheep served multiple purposes. They saved the manpower needed to mow the expansive White House grounds, freeing up workers for the war effort. But more importantly, they contributed to the Wilsons' carefully cultivated image as a rationing American family.

The first family went to great lengths to demonstrate their commitment to conservation. They stopped hosting receptions, organized war bond rallies, occasionally rode in a carriage instead of an automobile to save fuel, and participated in "wheatless Mondays" and "meatless Tuesdays." The sheep became the most visible symbol of these efforts.

““So far as attendants at the White House can recall, there never have been any animals around the White House, with the exception of dogs, cats, and squirrels,””

(This wasn't quite true—President William Taft had kept a cow, but the sheep were certainly unusual.)

The Wool Auction: A Fundraising Triumph

“I feel quite guilty for not writing to you long before this to tell you how much pleasure the sheep from Belair Farm have given the President and Mrs. Wilson. They have been admired by hundreds of people and they certainly make a beautiful picture on the White House lawn … I cannot tell you how much I appreciate all your kindness in letting the President have these sheep, which is deeply appreciated by both the President and Mrs. Wilson.”

But the sheep weren't just decorative. When shearing time came, two pounds of wool were given to each state. With governors acting as auctioneers, the wool was sold to the highest bidders across the country.

“From what I heard was bid, the cheapest was $100 per pound and the highest was $5,000 per pound. At any rate, I think it is safe to predict that Belair Farm sheep lead the world in the production of the most pricely wool.”

The total raised for the Red Cross was between $50,000 and $52,000, an extraordinary achievement that demonstrated both patriotic fervor and the power of presidential symbolism.

Not All Smooth Grazing

However, the sheep project wasn't without its challenges.

“ President Wilson is having no end of trouble with the flock of sheep he purchased recently to graze on the White House lawn.”

Not long after arriving at their prestigious new home, the sheep began falling ill. They caught pneumonia and the "dips"—likely stress-related ailments caused by the growing presence of automobiles in the capital, which scared them senseless. The noisy, unfamiliar vehicles of early 20th-century Washington were a far cry from the peaceful Maryland farm they'd left behind.

The sheep also proved to be enthusiastic landscapers, perhaps too enthusiastic. They tore up much of the back lawn and had to be moved to the front, where delicate flowers and trees were hastily fenced in to spare them from the flock's voracious appetites.

The End of an Era

By August 1920, after three summers of grazing and fundraising, the sheep were sold. Most were returned to William Woodward, though they remained highly sought after because of their presidential pedigree. Henry Oxnard received a ram that he assured President Wilson would be kept as a pet and "receive the best of care." Some of the sheep were later moved to Olney, Maryland, where they continued to provide wool for Wilson's admirers even after his death.

A Century Later: The Wool Returns Home

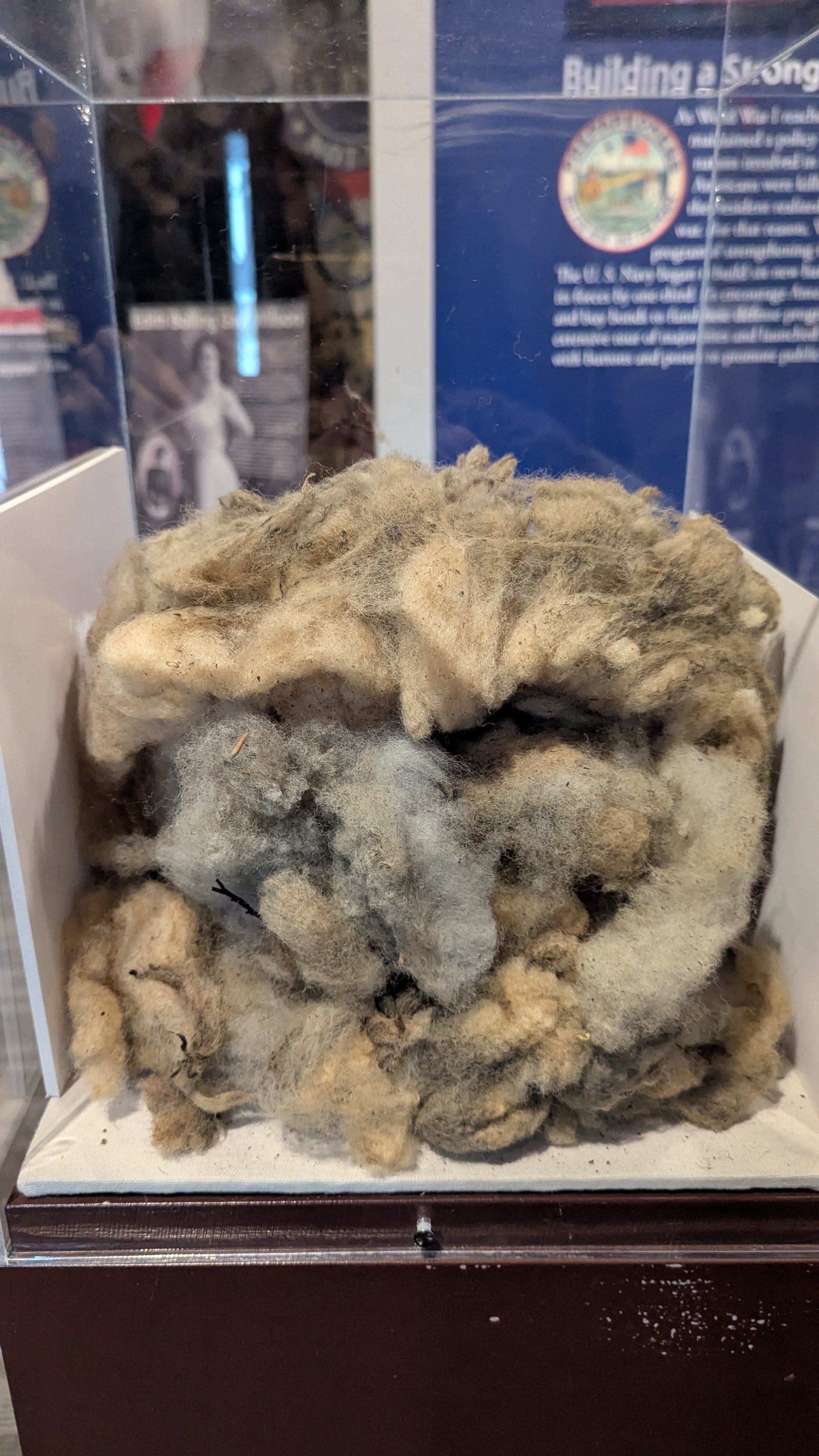

Over a century after those sheep first grazed on the White House lawn, their legacy took an unexpected turn. In 2018, the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library & Museum received a remarkable donation from the Donakowski family.

JP Brunschwyler, a West Virginia engineer and the father of Judith Donakowski, had been one of the people who bid on the presidential wool as part of a group in 1918. Rather than use it, he placed it in a safe deposit box, where it stayed for one hundred years.

This donation allows the museum to share a very tactile piece of history: actual wool from the sheep that once grazed in the president's yard, preserved perfectly across a century. Visitors can now see and appreciate this tangible connection to a unique moment in White House history.

A Legacy Beyond Wool

The story of Wilson's White House sheep is more than a quirky historical footnote. It represents a moment when the presidency adapted to extraordinary circumstances, when symbolism and substance merged, and when even the smallest gestures, or in this case, the woolliest ones, could contribute to a national cause.

Today, as we look back on this unusual chapter of presidential history, the sheep remind us that leadership sometimes requires creativity, that sacrifice was shared across all levels of society during wartime, and that even the White House lawn could serve the greater good.

The next time you see photos of the pristine White House grounds, you might just imagine a flock of patriotic sheep, grazing peacefully in service to their country, one blade of grass at a time.

Visit the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library & Museum to see the preserved wool and learn more about this fascinating piece of White House history.

Wool on display in our museum