Chesterton, Reading Aloud, and the Enjoyment of Literature: A Glimpse of Woodrow Wilson at Leisure

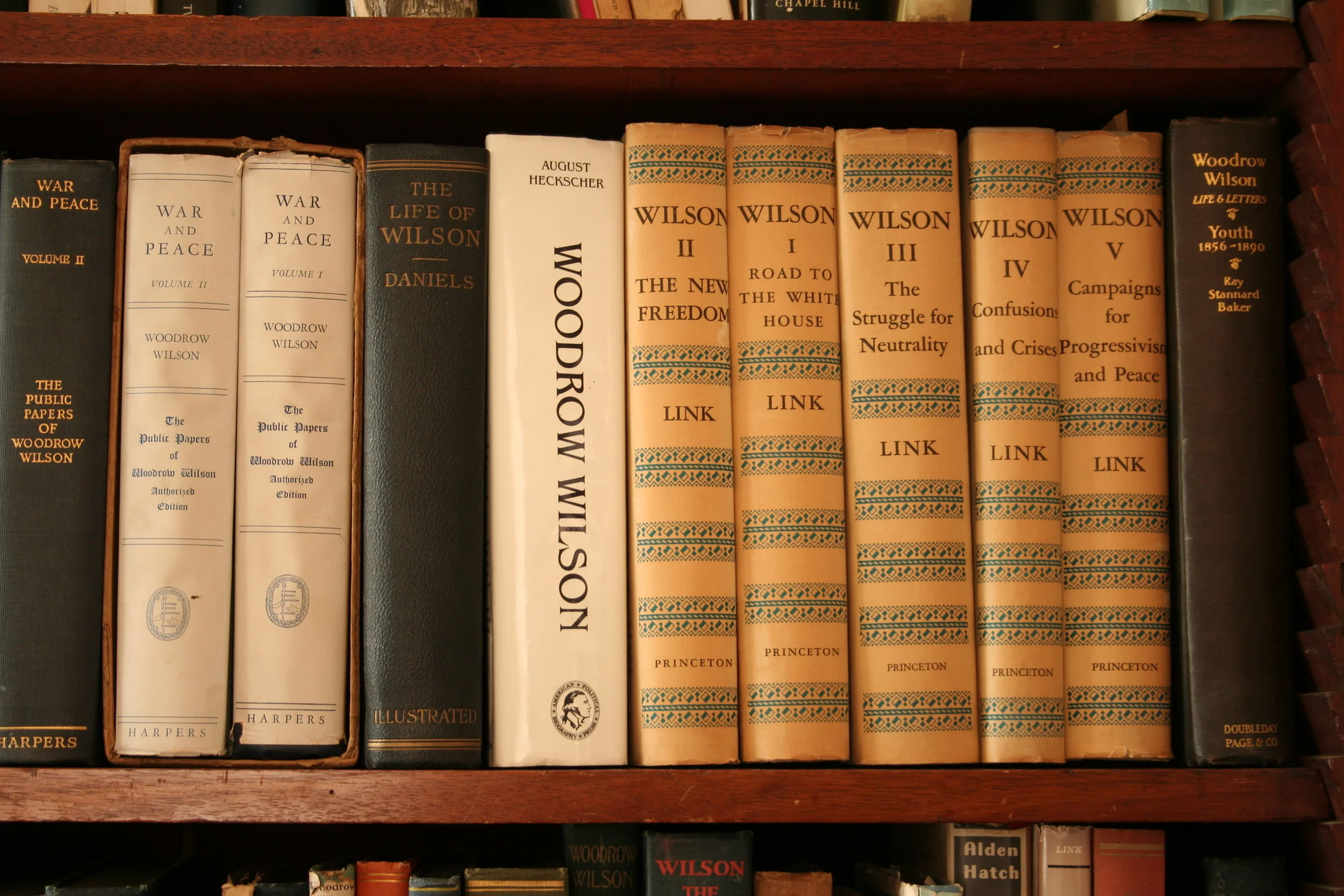

/Woodrow Wilson stands unique among American presidents because of his background in education. A man of letters before his political career, Wilson is the only president to have an earned PhD. His dissertation at Johns Hopkins University on American government was published in 1885 as Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics. It would be his first of numerous works on history, government, and the American political system.

Wilson’s intellectual pursuits are no surprise, considering that his father, the Presbyterian minister Joseph Wilson also appreciated the intellectual life. Among the collections of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library are books from Rev. Wilson’s library. Besides works of Biblical commentary and theology, there are works of great literature, such as Homer’s Iliad and the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Woodrow grew up in an environment where literature was shared and enjoyed.

Woodrow Wilson’s enjoyment of good books lasted throughout his life. As president, he often relaxed with his wife and daughters by reading aloud to them in the evenings. Wilson’s personal physician and Navy rear admiral Dr. Cary T. Grayson describe these quiet family moments centered around books. “He was never happier than in the bosom of his family, sitting before the fireplace in the Oval Room…. He was fond of reading aloud in modulated tones from his favorite authors.”

Woodrow Wilson, holding a book, with his first wife Ellen and their three daughters

A young Woodrow Wilson, between law school and graduate studies at Johns Hopkins

Wilson enjoyed a wide variety of authors and genres, from essays and philosophical works to poetry. One of his favorite poets was the British Romantic William Wordsworth. In a letter to his then fiancé, Ellen Axson, on August 23rd, 1884, Wilson quoted from Wordsworth’s “She Was a Phantom of Delight” including these lines, “The reason firm, the temperate will, / Endurance, foresight, strength and skill; /A perfect Woman, nobly planned, /To warn, to comfort, and command;” showing how he admired her intellect and saw her as a partner in his own ambitious pursuits.

Grayson notes that Wilson would often read John Burrough’s poem “Waiting” which encourages the ambitious person to be patient in the long wait until their goals are accomplished. Burrough writes that, “Asleep, awake, by night or day, / The friends I seek are seeking me; / No wind can drive my bark astray, / Nor change the tide of destiny.” To Grayson, this poem seemed to speak to Wilson personally. He says that Wilson found in it “perhaps a philosophy of his own life. ‘For, lo! My own shall come to me,’ as it did come before his death, after all the fluctuations of rejection and acceptance by the world’s opinion.”

Wilson read many dense works of literary criticism, political theory, history, and philosophy. Some of these titles, many of them still considered to be world classics today, were listed as part of his undergraduate courses at Princeton (then New Jersey) University. The books he read there included the English epic Paradise Lost by John Milton, the chapter from Cicero’s On Duties called “About the Tension of Honesty and Utility”, Rene Descartes Discourse on Method, and Aristotle’s Ethics and Politics. Outside of school, Wilson enjoyed reading essays discussing and critiquing various political philosophies as he notes in his shorthand diary on July 19th, 1876, saying that “Read Macaulay’s essay on Mill’s theory of government – a very able and extremely interesting article. He certainly shows Mill off to a great disadvantage.” Wilson follows this by remarking “How absurd Mill’s theory of government was[,] to be sure.” While hardly what we might think of as light summer reading, the essays by Thomas Babington Macaulay and Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire suited the young Wilson more than fiction. He confesses to his diary that “Most novels tend to do more harm than good. They have a tendency to make me gloomy.”

That is not to say that Woodrow Wilson did not enjoy fiction and poetry as well. In an article following his election as president, William G. McAdoo, the vice-president of the Democratic National Convention, described “The Kind of Man Woodrow Wilson Is.” Among other interests and qualities, McAdoo remarked on the literary interests of Wilson, saying that “ Mr. Wilson has the same unwearied delight in rereading his favorite authors, the speeches of Burke, the essays of Bagehot, Augustine Birrell, Gilbert K. Chesterton, poems of Wordsworth and Browning, and passages from his favorite Shakesperian (sic) play “Henry the Fifth”. Woodrow Wilson’s writing is littered with references to Shakespeare. Even during the busy months following the U.S. entrance into World War I, Wilson took the time to send a short, but humorous letter to one M. Clemens of Brooklyn, N.Y., arguing that as Shakespeare finished sentences with prepositions occasionally, the “rule that a sentence shall not end with a preposition is a mere piece of rhetorical affectation.” Even at the height of his political career, Wilson had not lost his interest in literature and the classics. Or his sense of humor.

As governor of New Jersey, Wilson sits in front of a book case, accompanied by his private secretary Joseph P. Tumulty.

While many of the authors Woodrow Wilson enjoyed were from the past, one of them was a contemporary. This was the British author, G.K. Chesterton. About two decades younger than Wilson, Chesterton was a popular essayist and journalist of his time. Chesterton was among the authors from which Wilson read aloud to his family in the evenings. Dr. Grayson saw parallels between the political philosophy of Woodrow Wilson and Chesterton’s thought on the topic. According to Grayson, Wilson found in the “glittering paradoxes” of Chesterton “a good deal of his own philosophy of progressive conservatism.” Both Chesterton and Wilson praised and expounded the concept of democracy in their words. An example from Chesterton is his paradoxical comparison between democracy (which seems inherently progressive) and tradition (which seems inherently conservative). For Chesterton, they are inextricably linked when he says “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead,” going on to explain that “Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our father.” Wilson likewise saw democracy as the means by which everyone, including the common man, could make his opinion known in the operation of government. In a lecture on democracy which he gave many times, Wilson said “Democracy’s advantage… is its variety and symmetry of development, its fullness of opportunity and richness of material. In it, not a few men of privileged blood only, but all men of original force are quickened to make the most of themselves.” In other words, democracy gave every citizen the opportunity to become a leader.

G. K. Chesterton at work

Wilson saw education as a crucial part of this “self-preparation” that is “the stimulating law of success for every man.” For Wilson, the ability to administer government, which in America was not limited to a certain blood line of aristocrats or monarchs, stood on the grounds of qualification rather than pedigree. While the people of the democracy were represented by and certainly influenced their government, the persons making the day-to-day decisions of government operation were qualified by their study and pursuit of statesmanship.

Wilson’s interest in literature, the classics, and education, as evidenced in his leisurely and academic pursuits throughout life, were an essential part of his vision for statesmanship. As the only American president with his entire career in academics prior to politics, it comes as no surprise that Wilson emphasized the well-trained mind of a good leader. He believed that America could not survive without “a firm love of order on [the part of the people], a sagacious insight into the character of men, and a steady preference for openness and honesty in the conduct of affairs.” If the people lost these values, “the whole structure would go presently to pieces.” Reading good literature was one way in which the statesman could gain insight into human nature and thereby learn how to be a good leader. For Wilson, the great books provided not only pleasant times of leisure with his family, but also the tools that he needed to serve the country as commander-in-chief.

Bibliography (Works Referenced)

Burroughs, John. “Waiting”. All Poetry, accessed July 11, 2025. https://allpoetry.com/poem/8491803-Waiting-by-John-Burroughs

Chesterton, G. K. Orthodoxy. Middletown, DE: Compass Circle, 2018.

Grayson, Rear Admiral Cary T. An Intimate Memoir. Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, 1977.

McAdoo, W.G. “The Kind of Man Woodrow Wilson Is”. The Century Magazine, Volume LXXV (85), Nov. 1912-Apr. 1913. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106010577952&seq=773

Wilson, Woodrow. “Shorthand diary entry Wednesday, July 19, 1876”. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Vol. 1. Ed. Arthur S. Link. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966.

----- “Shorthand diary entry Thursday July 13, 1876”. Papers, Vol. 1. Ed. Link.

----- “Letter to M. Clemens, November 27, 1917”. Papers, Vol. 45. -----

----- “Democracy: A Lecture”, December 5, 1891. Papers, Vol. 7. -----

Wordsworth, William. “She was a Phantom of Delight”. Quoted by Woodrow Wilson in “Letter to Ellen Louise Axson, August 23, 1884”. Papers, Vol. 3. Ed. Arthur S. Link. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966.