Red Summer of ‘19

/While Woodrow Wilson was off in Paris, working on the peace negotiations with other world leaders, troubles brewed at home. The high cost of living became a common complaint over the course of 1919 as the economy felt the disruptions of war and then sudden peace. This is in the midst of the uproar over the mail bomb plot that was discussed in an earlier post.

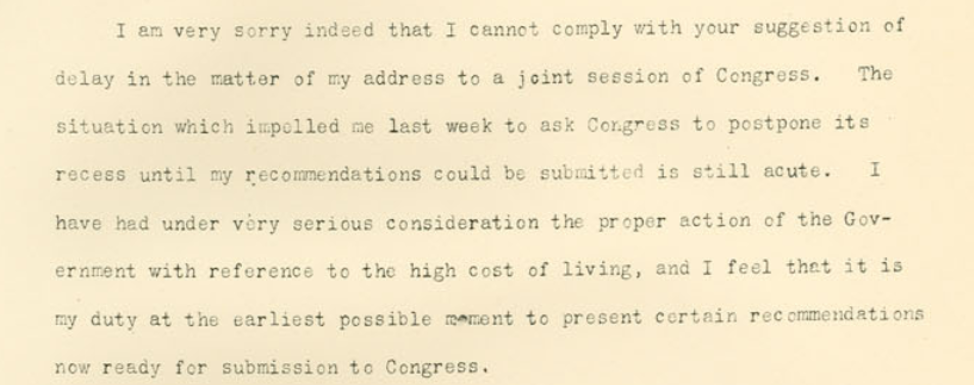

Cost of Living Data, August 13, 1919

Wilson received news of labor unrest early on. A letter from a newspaper in Rhode Island cabled to the President on April 16th appealed to him directly.

We know that you have larger problems in hand, but telephone strike in New England threatens to produce a general strike in all industries. This deserves your personal attention as one of the great questions of the day in the United States.

He would eventually address some of the problems with a letter to Congress. Industry was called to be mindful of the needs of workers and the new relationship they had as voters with the federal government. After President Wilson returned to the United States, he spoke to Congress in July about the agreement that he and many others had worked on.

The atmosphere in which the Conference worked seemed created, not by the ambitions of strong governments, but by the hopes and aspirations of small nations and of peoples hitherto under bondage to the power that victory had shattered and destroyed.

In the next month, in addition to pushing for the Senate to ratify the League of Nations agreement, he was able to spend time getting started on concerns of Americans that sumer, such as proposing some solutions to Congress about the high cost of living. He also appealed to the leaders of the workers in industry to keep their demands modest.

One thing that President Wilson had very little to say about, though, was the many incidents of racial violence that occurred that summer, which came to be known as Red Summer because of the shocking riots and lynchings that victimized African Americans. With the economic disruptions and the presence of returning veterans, some of them African Americans in uniform, a large number of towns witnessed some of the worst mob violence in their history, much of it instigated by angry crowds of white people. Certainly, taken as a whole, that summer was a dreadful highpoint in a surge of such attacks in the early part of the twentieth century that marked the worst racial violence since the days of Reconstruction. Red Summer, however, often has been overshadowed by the Tulsa Massacre of 1921 and the East St. Louis Riots of 1917.

One notable component of these events in 1919 is that there were cases recorded in the newspapers of African Americans, some of them trained veterans, defending their neighborhoods, something that was not written about very much in earlier attacks. A group of museums in Chicago have put together a dramatic digital exhibit of the riot that started there in July of 1919, discussing this aspect at length.

On his western tour to rally support for the League of Nations, Woodrow Wilson said in a speech in Helena, Montana on September 11:

I hope you won’t think it inappropriate if I stop here to express my shame as an American citizen at the race riots that have occurred at some places in this country, where men have forgot humanity and justice and orderly society and have run amuck.

This was in line with his general horror at mob violence, but it also reflects, in a way, the President’s unwillingness to take any executive action on the issue. Despite appeals from many groups and calls for a congressional investigation, Wilson continued to insist that it was a problem for local authorities. The president did not do very much, and then when he suffered a stroke shortly after the summer was over, any federal response came without direction from him.

Florence Randolph and Lizzie Pearce to Woodrow Wilson

A furious statement about the situation came from the renowned scholar, W.E.B. Du Bois. Completely reworking an earlier essay on white colonialism, Du Bois made it clear with “The Souls of White Folks,” in 1919, that he thought that imperialistic views of white supremacy sat at the heart of the World War and the attacks by violent mobs on innocent American citizens.

Conceive this nation, of all human peoples, engaged in a crusade to make the "World Safe for Democracy"! Can you imagine the United States protesting against Turkish atrocities in Armenia, while the Turks are silent about mobs in Chicago and St. Louis; what is Louvain compared with Memphis, Waco, Washington, Dyersburg, and Estill Springs? In short, what is the black man but America's Belgium, and how could America condemn in Germany that which she commits, just as brutally, within her own borders?