Prohibition and President Wilson: From the Dry Crusade to the Volstead Act

/Woodrow Wilson once told a humorous story that captured the spirit of pre-Prohibition America: “In Maine, before prohibition took hold, there was a popular brand of whiskey that made one intoxicated immediately, known as "squirrel whiskey." A fellow who had imbibed this potent drink developed a sudden desire to travel and boarded a train at the local station. His worried friends wired the conductor, describing him as a drunk man who didn't know where he was going, requesting that he be put off and sent back on the next train. The conductor wired back: "Impossible; there are several men on this train so drunk that they can't tell their names or their destination."

This anecdote reflects the reality of alcohol consumption in early America and hints at why the temperance movement gained such powerful momentum in the years leading up to national Prohibition.

The Rise of the Dry Crusade

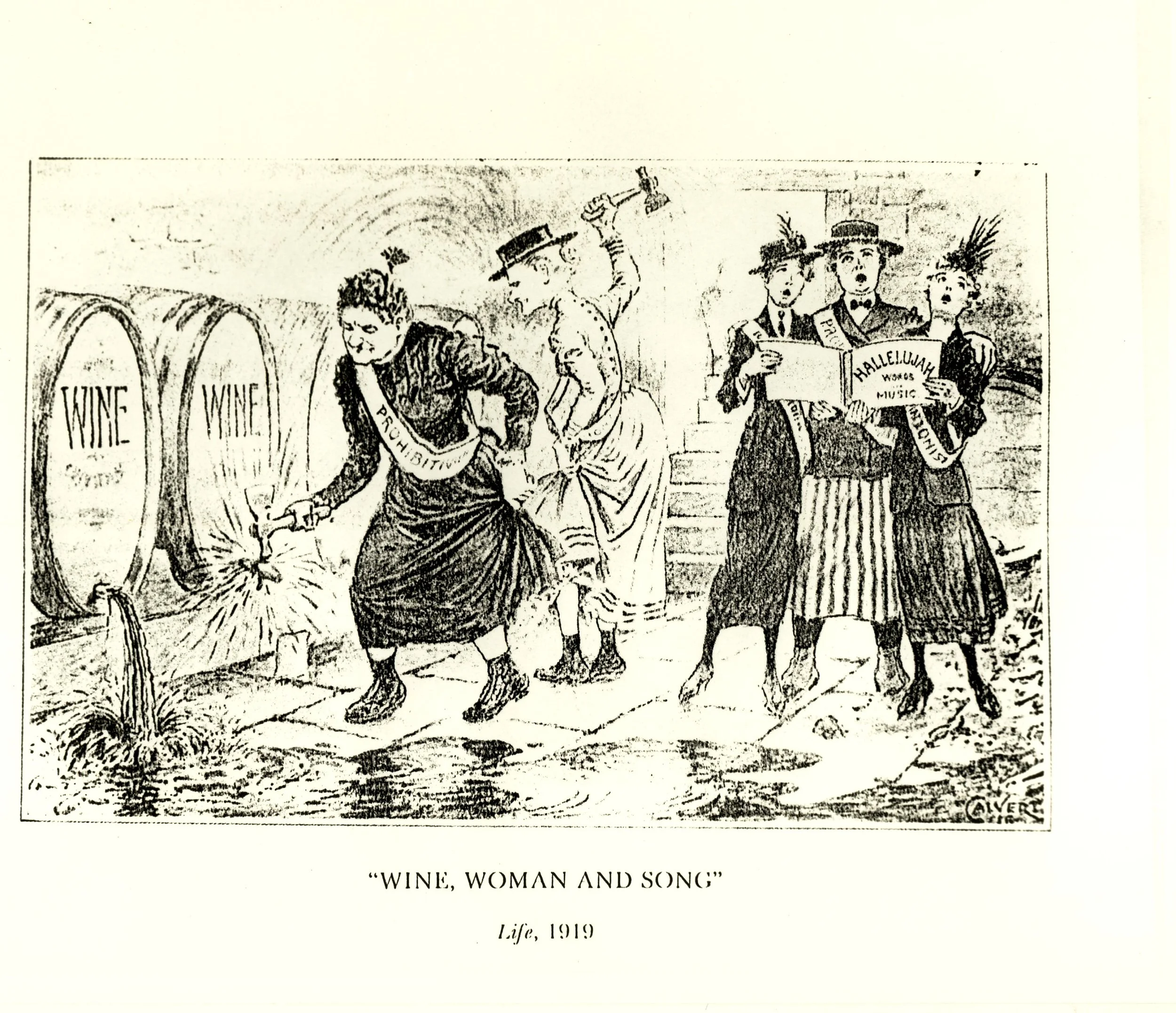

In the first decades of the eighteenth century, people in the United States drank more than a bottle and a half of hard liquor each week, far more than today. As Americans recognized that excessive drinking contributed to numerous social problems, it came to be seen as an enemy to the moral rectitude of the American home. Temperance societies and religious groups fought to limit access to alcohol by the 1830s, but it was really after the Civil War that organizations concerned with other causes such as women's rights and abolition turned their attention to what became known as the dry crusade.

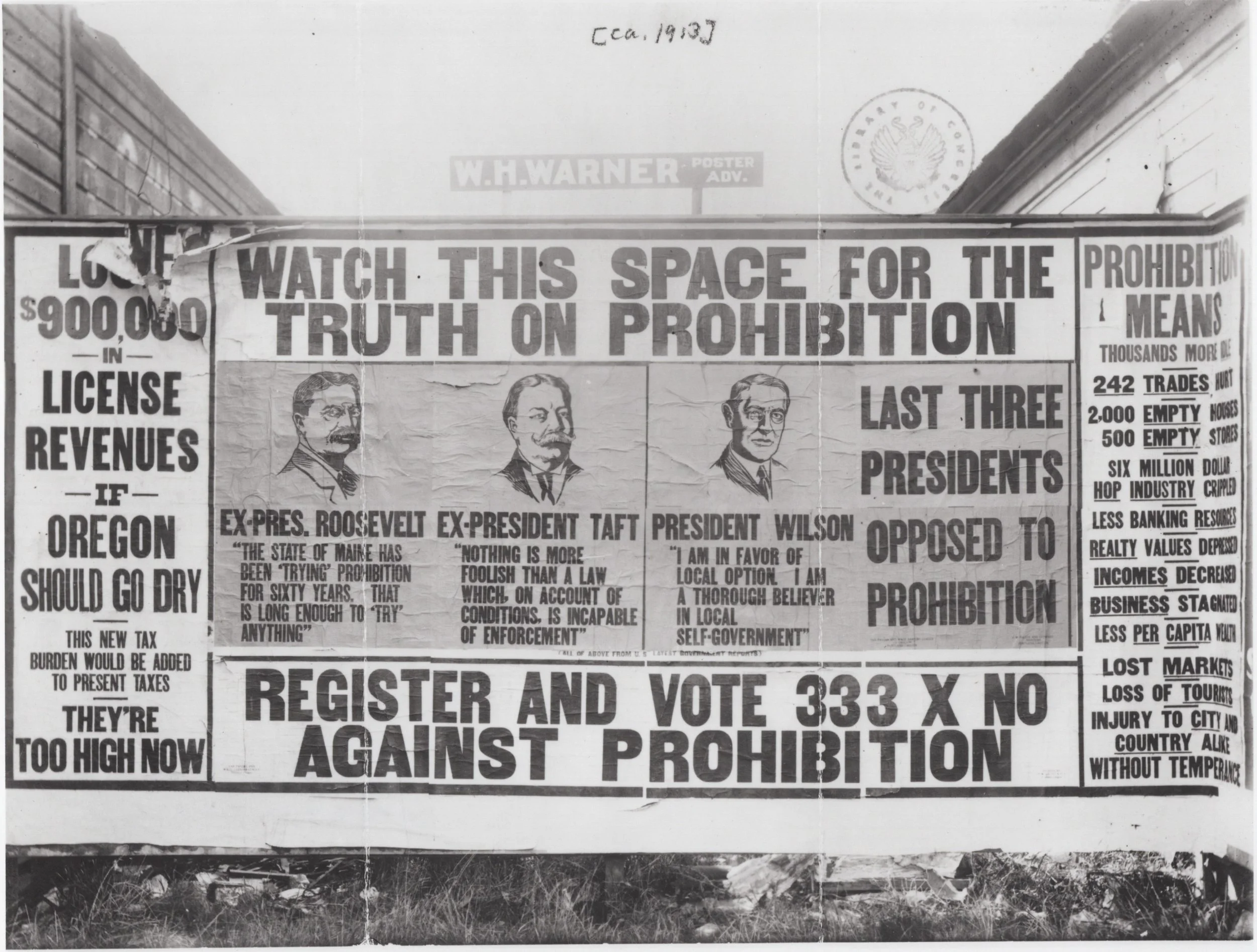

During the Progressive Era, temperance evolved from a moral crusade into a political powerhouse. Not only did a wide swath of voters agree that there should be legal limits on access to alcohol, but it also proved to be a very effective single issue to campaign on in states that were otherwise equally divided. Progressive reformers saw alcohol as a barrier to social improvement and believed that controlling its consumption would address everything from domestic violence to poverty to workplace accidents.

Wilson's Reluctant Involvement

For his part, Woodrow Wilson largely agreed with the moral benefits of controlling liquor, but he felt strongly that it was not a federal issue. He believed such matters should be left to state and local governments. Wilson remained loathe to step into the contentious politics of prohibition throughout his presidency. He in fact kept his own wine cellar, and said, as his physician Cary Grayson recorded in his diary, "I notice in the papers that the States wanted to confiscate liquors and wines that have been stored in private residences. I think that is interfering with personal privileges."

Wilson's personal stance reflected his broader political philosophy: he was never an outspoken supporter of either the "wet" or "dry" positions, and even took care to avoid the polarizing debate in his 1916 election campaign. However, Wilson was a firm believer in progressive action and lawmaking, and was an outspoken supporter of civil liberties.

World War I Changes Everything

The First World War, with its sweeping economic legislation, brought brewing and distilling under the umbrella of presidential responsibilities. An Army Bill in May of 1917 stated that it was within the President's power "to make such regulations governing the prohibition of alcoholic liquors in or near military camps and to the officers and enlisted men of the Army as he may from time to time deem necessary."

Even so, Wilson approached the issue cautiously. A 1918 report on brewing stated that "the social habits and political prejudices associated with this trade are still so deep-rooted, though steadily weakening, that entire prohibition should be the result of deliberate legislation rather than of an administrative decree." President Wilson agreed with this assessment, preferring to let Congress and the states take the lead.

Further calls for the control of drinking by the troops and of the supplies that went into brewing brought about a general limit on the sale of alcohol for the entire country. Wartime Prohibition was actually signed a week after the fighting stopped and came into effect a year later. The year 1919 also witnessed the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, setting the stage for nationwide prohibition.

Wilson's Veto of the Volstead Act

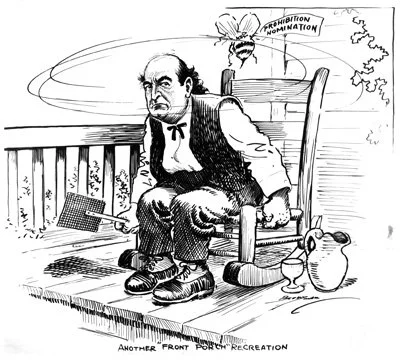

In 1919, the United States was technically still at war because Congress had rejected the famed Versailles Treaty, which Wilson had worked so hard to pass. So when the Volstead Act was passed by the House and Senate and set before Wilson in October of 1919, it contained two sections: one that provided for the enforcement of the new Constitutional Amendment, and one that sought to enforce Wartime Prohibition, even though most Americans considered the war over.

That October, President Wilson was slowly recovering from a massive stroke he had suffered not a month prior but felt motivated to take a position against the Volstead Act. He took issue with the second part of the Act that called for enforcement of wartime measures, which he felt were now unnecessary. In his official veto of the Volstead Act, Wilson warned that when dealing with matters that affected the "personal habits and customs of large numbers of our people," it was more essential than ever that legal procedure be taken most seriously.

Wilson's veto attempt was ultimately informed not by the size of his wine cellar, but by his desire to protect the rights of citizens from improper legislation. His largely technical civil liberties argument, however, was of no matter to the House of Representatives, who overrode his veto just two hours after receiving it. The Senate agreed and the Volstead Act became law on October 28, 1919, coming into force in January of the next year.

The Law and Its Consequences

The Volstead Act certified "intoxicating liquors" to be any substance that contained over 0.5% alcohol. Many in the country, including people from counties that had been dry for decades, hoped that prohibition would ease the country's ills. The issue remained a central focus of American politics until the Great Depression.

One reason prohibition remained so controversial was that alcohol remained available in so many places. Prohibition did not stop alcohol from reaching the streets. As AJ Jennings wrote to his friend from Chicago a year later, "And Ed you can buy real whiskey for 2.50 a quart. Canadian Club."

The Prohibition Amendment became the only addition to the United States Constitution to inhibit a freedom rather than expand one. While it did decrease alcohol consumption, it also created a boom in organized crime and corruption. As many people, both serious observers and skeptics, had predicted, the United States eventually turned against the Volstead Act because it came to be seen as a brake on economic recovery and an insult to the rule of law.

President Harding would later see Congress' Knox-Porter Resolution finally allow for a formal treaty signing with minimal pomp or circumstance between America and Germany in Berlin on August 25, 1921. But the legacy of Prohibition would haunt American politics and society for more than a decade, ultimately being repealed in 1933 during the depths of the Great Depression.

Conclusion

Woodrow Wilson's relationship with Prohibition reflects the complexities of the era and the tension between progressive reform, personal liberty, and federal power. While he sympathized with temperance goals, Wilson remained skeptical of federal overreach and concerned about civil liberties. His ultimately unsuccessful veto of the Volstead Act demonstrated his commitment to these principles, even as the nation embarked on one of its most ambitious and controversial social experiments. The story of Prohibition during the Wilson presidency reminds us that even well-intentioned reforms can have unintended consequences when they fail to account for the diverse habits and values of a large, pluralistic society.